Last month, the Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI) and Oxfam brought together brands, retailers, and stakeholders, from across the apparel and textile sector for ReDress: Fashioning a Fairer Future – a focused discussion at the intersection of circular fashion and human rights.

Through global expert panels, collaborative mapping and deep discussion the aim was to strengthen our understanding of emerging circular supply chains: who is involved, what they do, where it takes place – and crucially how to ensure decent work.

Why circularity needs a human rights lens

Circular apparel and textile models – whether recycling, resale, repair or rental - are often framed as environmental solutions to the industry’s outsized impact on the planet. Yet, at every stage of these systems are people. These supply chains rely on labour-intensive processes, frequently taking place in informal or hidden contexts. As per the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and ILO conventions, these workers have rights – regardless of where they are in the chain.

Our goal with ReDress was to bring a just transitions perspective to the conversation: making visible the people powering circular supply chains and placing decent work at the heart of circular fashion's future.

Mapping circular supply chains

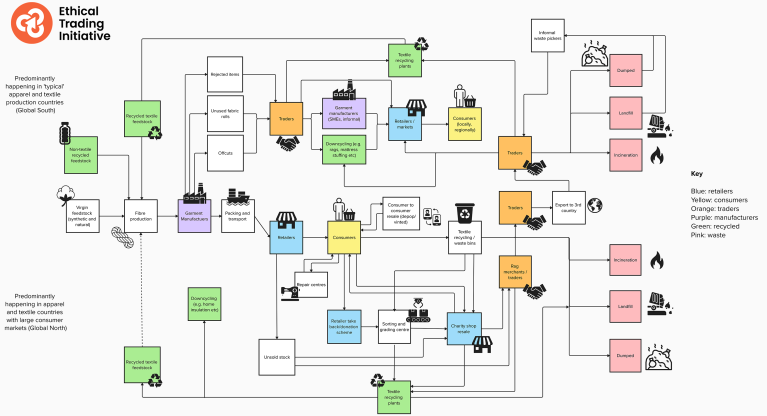

Despite the excitement and energy around circular fashion, a lot is still unknown about exactly what it involves, where and with whom. To kick off, we shared an early-stage visual map of circular supply chains developed with organisations working in this space. But participants quickly helped us improve it.

For example, currently items returned to retailers are missing from the map. Often they join ‘unsold stock’ which may be donated to charity partners, or sold to traders for export to third countries for resale. In addition, ‘white labellers’ are also missing – third parties that remove all branding and labels from for example unsold stock, so it can be resold by other players, such as outlet stores. Perhaps most crucially the diagram currently underplays the sad reality that a significant proportion of clothing is simply binned by UK consumers when they’ve finished with it, bypassing options such as consumer-to-consumer resale, charity shop donation, and recycling, and instead heading straight for landfill or incineration.

Urgent need for collaboration

The examples cited above focus on the post-production, post-retail stages, but of course waste is generated at production stages too – represented in the top half of the map. Organisations such as Reverse Resources and the Centre for Child Rights and Business are doing excellent work to bring visibility to this, and to shift the narrative from a focus on ‘waste’ to a focus on ‘resources’ and opportunity. Oxfam Cambodia and Oxfam in Bangladesh are also looking more at this space, and the role of informal workers.

But one of the challenges here is that material, whether seen as waste or resource, is quickly amalgamated, making it is almost impossible for individual companies to trace what happens to offcuts and unused rolls generated in the production of their items. Understanding what is going on, where, and who is involved, is probably impossible for one company to resolve.

The solution lies in collaboration: horizontal collaboration between peer brands and retailers with shared suppliers and supply chains; and also in vertical collaboration between suppliers and buyers. But this will take time, and suppliers are already burdened with a multitude of reporting requirements from buyers: this can’t be another extractive demand from on high. Trust and a commitment to long-term genuine partnership is needed from all.

Learning from existing circular models

While “circular fashion” may feel new in boardrooms or policy circles, it has long existed in various forms in global majority contexts. Offcuts and unused fabric rolls are used to produce new items sold in local and regional markets. Smaller scraps are upcycled by artisans into handcrafted products for niche markets, and downcycled into stuffing for mattresses and cleaning cloths, for example. Traders in urban centres buy bundles of second hand items and sell what they can on market stalls. And new but rejected items make their way from garment factories to local markets and consumers.

These practices generate value from resources that would otherwise have been wasted. None singlehandedly address the environmental and climate impact of the apparel and textiles sector, but collectively they make a contribution, and they offer important lessons – about innovation, opportunity, and equity. These should inform decision making around circular fashion. But too often these perspectives and voices, largely but not exclusively located in global majority countries, are overlooked.

A just transition requires listening to, learning from, and partnering with those already practicing circularity. There is an opportunity here for decision-makers whether within business, industry, policy-making or advocacy to invite these perspectives to the table – aligning with the principles of just transition and the commitment of the Sustainable Development Goals to ‘leave no-one behind’.

Informality and workers’ rights

One of the most pressing concerns raised at ReDress and flagged in research to date, is that many roles in existing stages of circular supply chains – sorting, grading, remanufacturing, resale – are employed informally and often denied their right to decent work. This cannot be ignored. If we are serious about sustainability, we must be equally serious about securing decent work in these emerging spaces. That includes: fair wages, safe working conditions, and freedom of association.

This challenge is far from insurmountable. Civil society organisations and trade unions already support workers in informal sectors. Brands and retailers have a vital role to play – not by controlling the process or closing down vital livelihood opportunities for vulnerable workers, but by co-investing in collaborative, long-term solutions that prioritise worker agency.

Embedding human rights due diligence in circularity

The UN’s Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights requires businesses to undertake human rights due diligence in their supply chains. As these supply chains become more circular, so too does the scope of HRDD. Currently many decisions regarding circularity are shaped by environmental priorities, without input from human rights specialists. But environmental and human rights goals are not separate – they’re mutually reinforcing. Circularity cannot truly be sustainable without labour rights at its centre; internal business structures must reflect this.

From capsule to core

Several participants noted that circularity must move from the margins of business strategy to its centre. As long as circular models remain limited to niche collections or pilot projects, their impact will be limited. True transformation means rethinking overproduction and overconsumption. In an era when consumers have increased the scale of their wardrobes and reduced the number of times they wear an item, it means involving marketing, alongside design and buying teams, in reimagining what value looks like and what responsible growth entails. This level of change is complex, but necessary.

No circularity without people

People often ask about the ‘business case’ for sustainability. For ETI and Oxfam, this question misses the point: human rights aren’t optional – they’re enshrined the ILO’s fundamental principles and rights at work, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

But, if a ‘business case’ is still helpful in some quarters, it’s this: there is no business without people, there are no supply chains without workers. People make circular systems possible—from factory to market stall, repair shop to recycling plant - it’s time to take their contributions and their rights seriously.

At ReDress, Dr Halima Begum, Oxfam GB CEO, captured it perfectly:

“Moments like these might feel small as they happen, but when we look back in ten years, we will see that they were part of the work in stitching a fairer future. Each idea exchanged contributes to the larger change we are all striving for.”

Thank you to everyone who joined us in this conversation. ETI and Oxfam with its colleagues in Bangladesh, Cambodia and other countries will continue to explore solutions to some of the challenges raised. But we can’t do it alone. Let’s keep going, together.